Businesses hoarding workers? Say what?

Chief Economist Eugenio J. Alemán discusses current economic conditions.

I am back from the annual NABE (National Association for Business Economics, www.nabe.com) conference in Chicago after spending three days listening to specialists in various sectors of the domestic and global economy talk about what they see today and what they expect in the future. I have been a member of NABE since 1989 and have been a board member in the past so I try to go every year and reconnect with a great number of colleagues and friends.

One of the many great benefits of being a member of NABE is that we normally have Federal Reserve (Fed) governors present at our events. At this last annual meeting in Chicago, we had two members of the Fed presenting at the conference, the president of the Chicago Federal Reserve, Charles L. Evans, who was the conference’s host, and Lael Brainard, the Vice Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Both of them mentioned the Fed’s strong commitment to bring down inflation as well as the fact that it was not going to waver in its steadfast objective of bringing down inflation.

However, I was somewhat concerned with some of the things I heard during the conference or the interpretation of some of the comments. This was not the first time I have heard these issues. One of these concepts is that of ‘labor hoarding.’ I have been hearing this concept of ‘labor hoarding’ for several months and the truth is that it makes no sense in the current context. Yes, there is a ‘labor hoarding’ concept that has been around since the 1960s. This concept explains that companies tend to stick to workers in the short run due to the cost of hiring, training, and firing workers.

On August 4, 2022, an article in Bloomberg read “Labor hoarding holds key to how severe a U.S. recession may get.” On September 8, 2022, an article in www.thehustle.com was entitled “Layoffs are out. Labor hoarding is in.” Inc.com has an article called “Why economists are talking about ‘Labor Hoarding’ and what you need to know about it.”

I could continue to point to such articles during the last couple of months, but I think that these examples suffice. During the NABE conference, Vice Chairman Lael Brainard said, according to the New York Times article titled “Companies Hoarding Workers Could Be Good News for the Economy,” that “Businesses that experienced unprecedented challenges restoring or expanding their work forces following the pandemic may be more inclined to make greater efforts to retain their employees than they normally would when facing a slowdown in economic activity.”

Vice Chair Brainard said that firms may think twice about letting go workers because of the “unprecedented challenges” suffered in restoring workers after the pandemic. She was not saying that companies are hoarding workers today, only that they may decide to not get rid of workers as fast as they have done in the past when faced with recessions, especially after the difficulty they have recently experienced with the recovery from the pandemic recession.

Again, the labor hoarding concept in economics has existed for many decades and is related to the concept of efficiency wages.

According to Jeff E. Biddle, labor hoarding “was presented as a profit-maximizing response by employers to costs of hiring, firing, and training workers, and thus as an explanation of procyclical labor productivity.” According to an ECB Monthly Bulletin from July of 2003 “Labour hoarding can be defined as that part of labour input which is not fully utilized by a company during its production process at any given point in time. Under-utilisation of labour can manifest itself in various forms, such as reduced effort or hours worked, and the shift of labour to other uses, such as training. From the company’s point of view, some labour hoarding may be optimal given the fixed costs associated with adjusting staff numbers. These costs include costs of recruitment, screening and training of new workers, as well as costs related to the termination of contracts such as severance pay.”

That is, in layman terms, labor hoarding is related to how costly it is to hire, train, and fire workers. Typically, the higher the fixed costs of hiring, training, and firing workers, the longer it takes for a firm to get rid of workers when faced with a slowdown in economic activity.

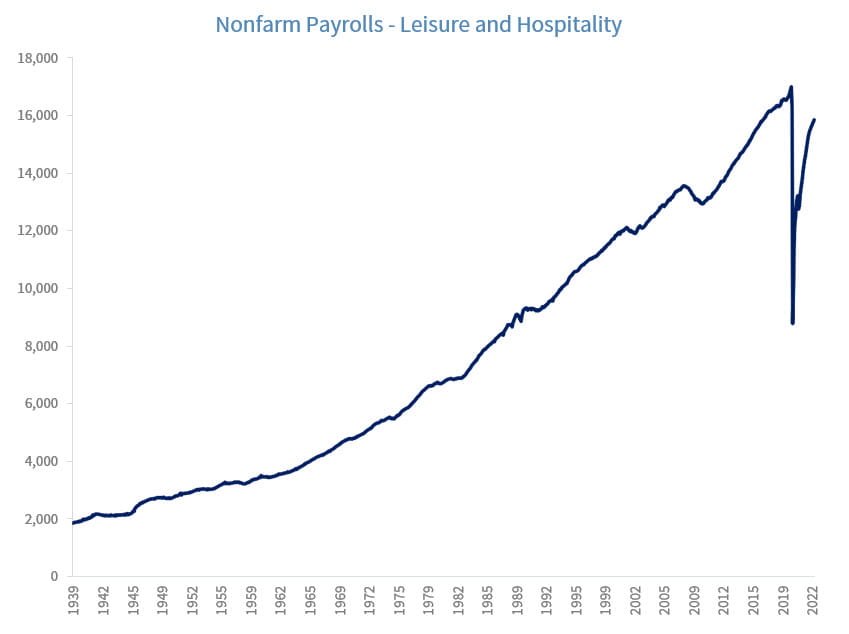

However, is this what is happening today? Definitely not, companies are not hoarding labor today, they are still just trying to go back to ‘normal’ levels of labor input, especially in the service sector. This is particularly true in the leisure and hospitality sector, which is the sector that has seen the highest increase in wages and salaries. The leisure and hospitality sector is still 1.138 million jobs below the level of employment in February of 2020, just before the pandemic even though nonfarm payroll jobs have already recovered to pre-pandemic levels.

Recall that labor costs are about 60% to 70% of the total costs of doing business so businesses don’t take employment decisions lightly, especially small businesses. Before wearing my economist hat, I managed a small business and was a small business owner during several decades, so I know how difficult these decisions are for businesses and for their survival.

While it may be true that some firms may decide to keep workers for some time when faced with a slowdown in demand, this cannot last for long. If you are a large firm and you have plenty of financing available, you may be willing to ‘hoard’ workers for some time before finally deciding to lay them off, but this is probably not an alternative for small businesses, which hire ~50% of all workers in the U.S. and have smaller profit margins than large businesses.

In fact, the last two recessions, in 2008 and 2020 are good examples of how fast businesses react to bad economic news by laying off workers as soon as they realize the economy is heading into recession. Of course, neither of these recessions were typical but they show that firms make decisions relatively quickly in order to survive.

What is happening today is not that firms are hoarding labor. What they are doing is just trying to get back to pre-pandemic levels and they are struggling to find workers. And this may, in fact, be good news going forward because if firms are still struggling to find workers to cover their employment needs (that is, they are not hoarding labor) then the probability is that they will have to layoff a reduced number of workers if faced with a recession or a slowing of demand for their products, which is very different than what many are saying businesses are doing, which is ‘labor hoarding.’

Economic and market conditions are subject to change.

Opinions are those of Investment Strategy and not necessarily those Raymond James and are subject to change without notice the information has been obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but we do not guarantee that the foregoing material is accurate or complete. There is no assurance any of the trends mentioned will continue or forecasts will occur last performance may not be indicative of future results.

Consumer Price Index is a measure of inflation compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Studies. Currencies investing are generally considered speculative because of the significant potential for investment loss. Their markets are likely to be volatile and there may be sharp price fluctuations even during periods when prices overall are rising.

Consumer Sentiment is a consumer confidence index published monthly by the University of Michigan. The index is normalized to have a value of 100 in the first quarter of 1966. Each month at least 500 telephone interviews are conducted of a contiguous United States sample.

Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCE): The PCE is a measure of the prices that people living in the United States, or those buying on their behalf, pay for goods and services. The change in the PCE price index is known for capturing inflation (or deflation) across a wide range of consumer expenses and reflecting changes in consumer behavior.

Consumer confidence index is an economic indicator published by various organizations in several countries. In simple terms, increased consumer confidence indicates economic growth in which consumers are spending money, indicating higher consumption.

The Consumer Confidence Index (CCI) is a survey, administered by The Conference Board, that measures how optimistic or pessimistic consumers are regarding their expected financial situation.

Leading Economic Indicators: The Conference Board Leading Economic Index is an American economic leading indicator intended to forecast future economic activity. It is calculated by The Conference Board, a non-governmental organization, which determines the value of the index from the values of ten key variables

Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc. owns the certification marks CFP®, CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™, CFP® (with plaque design) and CFP® (with flame design) in the U.S., which it awards to individuals who successfully complete CFP Board's initial and ongoing certification requirements.

Currencies investing are generally considered speculative because of the significant potential for investment loss. Their markets are likely to be volatile and there may be sharp price fluctuations even during periods when prices overall are rising.

The STOXX Europe 600, also called STOXX 600, SXXP, is a stock index of European stocks designed by STOXX Ltd. This index has a fixed number of 600 components representing large, mid and small capitalization companies among 17 European countries, covering approximately 90% of the free-float market capitalization of the European stock market (not limited to the Eurozone).

Geographical Revenues: Overall country-specific revenues as a percentage of total revenues from a specific index such as the S&P 500 or the STOXX Europe 600.

Source: FactSet, data as of 9/30/2022